AVAILABLE CABOCHONS

(Last updated 1/14/09)

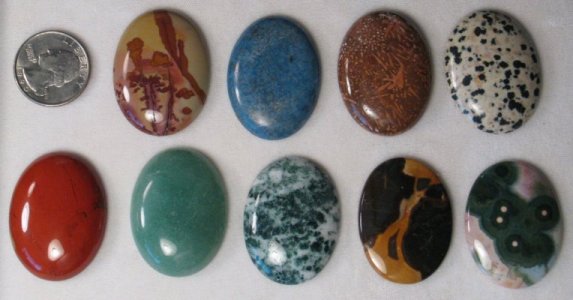

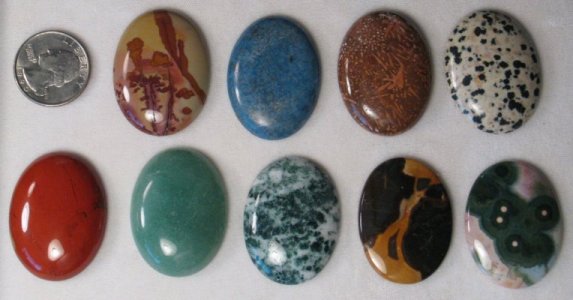

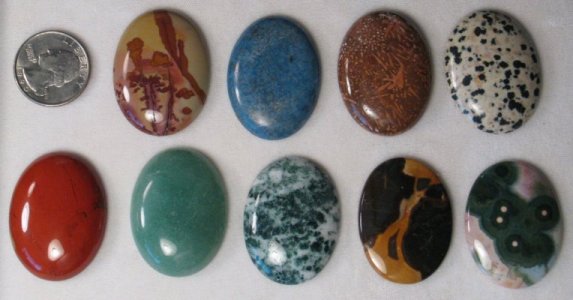

On this page I've illustrated just

a few of the many types of cabochons - numbering close to 1000

- that I have available for wire-wrapping. (Unfortunately most

of these pix were taken in artificial light, which caused visible

reflections, but colors are still reasonably true.)

Many different materials that show

interesting colors and patterns can be found in cabs of standard

sizes and shapes at very reasonable prices, including many different

types of agates and jaspers (see under Quartz in Gems-2).

An assortment of such stones is shown below, including flower

jasper (top center left), sodalite (top center; a mineral in its

own right), chrysanthemum stone (top center right; another non-quartz

stone), dalmatian jasper (top right), red jasper (bottom left),

mountain "jade" (bottom center left; actually a jasper),

tree agate (bottom center), and a few less common ones as well,

including Amazon Valley jasper (bottom center right) and ocean

jasper (bottom right). [Note the wide border on the pic below;

just click on the pic to see an enlargement.}

Sometimes it is cutting that adds

to the value of a material, as in the stones shown in the pix

below. I was fortunate enough to stumble into the booth of master

cutter Raul Rojas of Oro Grande, New Mexico at an open air gem

show in Buena Vista, Colorado and came away with these highly

polished yet incredibly thin (2.5 to 3.5mm) matching (and sometimes

mirror image) cabochon pairs that should make spectacular dangle

earrings. As you can see, Mr. Rojas used many different types

of stones and cut them into many interesting shapes, in addition

to selecting materials with marvelous, eye catching patterns.

Sometimes it is cutting that adds

to the value of a material, as in the stones shown in the pix

below. I was fortunate enough to stumble into the booth of master

cutter Raul Rojas of Oro Grande, New Mexico at an open air gem

show in Buena Vista, Colorado and came away with these highly

polished yet incredibly thin (2.5 to 3.5mm) matching (and sometimes

mirror image) cabochon pairs that should make spectacular dangle

earrings. As you can see, Mr. Rojas used many different types

of stones and cut them into many interesting shapes, in addition

to selecting materials with marvelous, eye catching patterns.

On the other hand, there are some

jaspers and especially agates that are truly exceptional. One

is Crazy Lace, which derives its name from the fine opaque to

translucent bands that swirl together to create complex and extremely

varied patterns. Much of the material found on the market today

has banding that tends to be various shades of white or gray with

creamy browns, blacks, golds, and occasional pinks or reds, but

material from older collections displays a much wider variety

of bright colors. Crazy lace comes primarily from Chihuahua and

other locations in northern Mexico; the Sierra Santa Lucia mountain

range just west of the village of Benito Juarez is particularly

famous for its production of "Mexican Crazy Lace."

On the other hand, there are some

jaspers and especially agates that are truly exceptional. One

is Crazy Lace, which derives its name from the fine opaque to

translucent bands that swirl together to create complex and extremely

varied patterns. Much of the material found on the market today

has banding that tends to be various shades of white or gray with

creamy browns, blacks, golds, and occasional pinks or reds, but

material from older collections displays a much wider variety

of bright colors. Crazy lace comes primarily from Chihuahua and

other locations in northern Mexico; the Sierra Santa Lucia mountain

range just west of the village of Benito Juarez is particularly

famous for its production of "Mexican Crazy Lace."

Another special agate is Laguna,

which comes from an area in Chihuahua, Mexico just east of Estacion

Ojo Laguna (Eye Lake), a tiny train stop about 150 miles almost

due south of El Paso, Texas; it is produced by about a dozen claims

running roughly north to south down a 4 mile stretch of the low

mountains located there. Laguna is a nodular "fortification"

type agate known for its tight banding and bright colors, and

is considered to be the most beautiful banded agate in the world.

The bands may be clear, white, or any other color; and

some specimens show over 100 individual bands per square inch.

Striking (and sometimes jarring) color combinations in the banding,

as well as subtle color shifts, are common. Fine specimens can

be very expensive, but I got these slices, well-polished and with

rounded edges - and with what I think are pleasing colors - at

a very reasonable price.

Another special agate is Laguna,

which comes from an area in Chihuahua, Mexico just east of Estacion

Ojo Laguna (Eye Lake), a tiny train stop about 150 miles almost

due south of El Paso, Texas; it is produced by about a dozen claims

running roughly north to south down a 4 mile stretch of the low

mountains located there. Laguna is a nodular "fortification"

type agate known for its tight banding and bright colors, and

is considered to be the most beautiful banded agate in the world.

The bands may be clear, white, or any other color; and

some specimens show over 100 individual bands per square inch.

Striking (and sometimes jarring) color combinations in the banding,

as well as subtle color shifts, are common. Fine specimens can

be very expensive, but I got these slices, well-polished and with

rounded edges - and with what I think are pleasing colors - at

a very reasonable price.

A "new" stone called Polish

Flint - grey to brownish grey in color and showing alternating

dark and light bands (often translucent) in striking patterns

- has recently become popular for use in jewelry, particularly

in Europe. A true flint - a hard cryptocrystalline form of quartz

categorized as a chert that occurs primarily as nodules in sedimentary

rocks such as limestone, it was used extensively for knapping

throughout prehistory. It comes from an area on the northern fringes

of the Swietokrzyskie (Holy Cross) Mountains in central Poland,

between the towns of Ilza and Ozarów, and many ancient

extraction sites and primitive mines are known, the largest and

most famous of the latter being Krzemionki, used by peoples of

many different cultures from ca 3900 to 1600 BC. The oldest finds

of this flint date to the Middle Paleolithic, but its widest distribution

occurred during the Late Neolithic when the Globular Amphora Culture

exported the material, mainly in the form of flint axes; its use

continued regionally well into the Bronze Age. In modern times

it was regarded mostly as a contaminant during the extraction

and making of lime from the limestone that contained it.

A "new" stone called Polish

Flint - grey to brownish grey in color and showing alternating

dark and light bands (often translucent) in striking patterns

- has recently become popular for use in jewelry, particularly

in Europe. A true flint - a hard cryptocrystalline form of quartz

categorized as a chert that occurs primarily as nodules in sedimentary

rocks such as limestone, it was used extensively for knapping

throughout prehistory. It comes from an area on the northern fringes

of the Swietokrzyskie (Holy Cross) Mountains in central Poland,

between the towns of Ilza and Ozarów, and many ancient

extraction sites and primitive mines are known, the largest and

most famous of the latter being Krzemionki, used by peoples of

many different cultures from ca 3900 to 1600 BC. The oldest finds

of this flint date to the Middle Paleolithic, but its widest distribution

occurred during the Late Neolithic when the Globular Amphora Culture

exported the material, mainly in the form of flint axes; its use

continued regionally well into the Bronze Age. In modern times

it was regarded mostly as a contaminant during the extraction

and making of lime from the limestone that contained it.

Among my favorite cabochons are

those produced from fossilized materials. The stones pictured

below are a type of fossiliferous silicified sedimentary rock

called mookaite, named after the principal locality where the

rock is dug, an outcrop along Mooka Creek on a sheep farm (Mooka

Station, covering ca 700,000 acres) located on the west side of

the Kennedy Range about 100 miles inland from the coastal town

of Carnarvon and 600 miles north of Perth, the capital of Western

Australia. According to locals, the Aboriginal word "mooka"

means "running waters," but the rock consists principally

of the remains of tiny marine organisms known as radiolaria,

countless numbers of which were deposited as sediment near the

shore of an ancient sea. These organisms possessed an unusual

skeletal structure of opaline silica; so when the sea retreated

the sediments were cemented into solid rock by silica originating

from the radiolaria themselves (and/or possibly from weathered

rocks nearby). The best material has properties similar to chalcedony,

and generally occurs as nodules lying in decomposed radiolarian

clay beneath the bed of the creek.

Among my favorite cabochons are

those produced from fossilized materials. The stones pictured

below are a type of fossiliferous silicified sedimentary rock

called mookaite, named after the principal locality where the

rock is dug, an outcrop along Mooka Creek on a sheep farm (Mooka

Station, covering ca 700,000 acres) located on the west side of

the Kennedy Range about 100 miles inland from the coastal town

of Carnarvon and 600 miles north of Perth, the capital of Western

Australia. According to locals, the Aboriginal word "mooka"

means "running waters," but the rock consists principally

of the remains of tiny marine organisms known as radiolaria,

countless numbers of which were deposited as sediment near the

shore of an ancient sea. These organisms possessed an unusual

skeletal structure of opaline silica; so when the sea retreated

the sediments were cemented into solid rock by silica originating

from the radiolaria themselves (and/or possibly from weathered

rocks nearby). The best material has properties similar to chalcedony,

and generally occurs as nodules lying in decomposed radiolarian

clay beneath the bed of the creek.

Other fossiliferous silicified materials

can be formed from various plant or animal remains in a way that

leaves their original structures intact. An example familiar to

most people is petrified wood, but many other materials can undergo

this process, as in the petrified algae colonies - called stromatolites

- shown in the pic on the left. The materials in the pic on the

right are all "gemfossils" as well. The black and white

cabs at top left are called "peanut wood," found along

the edge of the Kennedy Range in the "Windalia Radiolarite"

(the same geological formation that contains mookaite). Before

the wood - the main one being "Araucaria,"a podocarp

conifer that grew ca 70 million years ago - was petrified, it

was washed into the ocean as driftwood, then attacked by shipworms

(actually the marine bivalve Teredo) that eventually riddled the

entire piece with boreholes. When the wood became waterlogged,

it sank to the bottom of the ocean, settled into the mud, and

the boreholes filled with a light colored radiolarian sediment

before petrification began. The cab at top center left is called

feather agate, a petrified grass from the island of Sumatra (but

from a different part of the island than fossil coral); inclusions

resembling wheat stalks/seeds (or 'pea grass') are often visible.

The cab at bottom left is another type of petrified grass. The

two cabs at top right are petrified palm wood from the Oligocene

period (ca 38 to 23 million ago); it contains rod-like structures

within its regular grain - these can show up as dots, tapering

rods, or continuous lines, depending on the angle of the cut.

The best palm wood is found in Louisiana - it's their state fossil.

The cab in the center of the pic is a fossilized horn coral from

high in the mountains of Utah; this coral - in which the original

structure has been replaced by red agate - dates from the Silurian

Age (390 million years ago), and belongs to the extinct order

of corals called Rugosa. The three cabs at bottom right, also

from Utah, are cut from fossilized dinosaur bone; the cell structures

are clearly visible.

In addition to various types of

purely silica (ie, quartz) materials, interesting and beautiful

cabochons can be cut from many other types of rock that have a

high silica content. For example, rhyolite is an igneous (ie,

volcanic) rock that typically contains over seventy percent silica;

one of the most attractive is Apache Sage from New Mexico (left;

also called Mimbres Valley Picture Stone). And if rhyolite lava

is cooled too quickly to crystallize, it instead forms obsidian;

one of the most common is snowflake (left; the white inclusions

are radially clustered crystals of cristobalite; the best examples,

as in this piece, are also called flower), but many other examples

are known, including mahogany (center) and rainbow (right; oriented

by a master cutter so its color bands follow the shape of a heart)

In addition to various types of

purely silica (ie, quartz) materials, interesting and beautiful

cabochons can be cut from many other types of rock that have a

high silica content. For example, rhyolite is an igneous (ie,

volcanic) rock that typically contains over seventy percent silica;

one of the most attractive is Apache Sage from New Mexico (left;

also called Mimbres Valley Picture Stone). And if rhyolite lava

is cooled too quickly to crystallize, it instead forms obsidian;

one of the most common is snowflake (left; the white inclusions

are radially clustered crystals of cristobalite; the best examples,

as in this piece, are also called flower), but many other examples

are known, including mahogany (center) and rainbow (right; oriented

by a master cutter so its color bands follow the shape of a heart)

Nundoorite (top), from an area near

Nundle, Australia, is also mostly quartz, but contains the minerals

andalusite and epidote (the green spots) as well. A stone with

a similar composition is unakite (bottom; named after the Unakas

mountains of North Carolina, where it was first found), another

of my favorites; an altered granite, it is mostly quartz, but

also contains pink orthoclase feldspar and green epidote.

Nundoorite (top), from an area near

Nundle, Australia, is also mostly quartz, but contains the minerals

andalusite and epidote (the green spots) as well. A stone with

a similar composition is unakite (bottom; named after the Unakas

mountains of North Carolina, where it was first found), another

of my favorites; an altered granite, it is mostly quartz, but

also contains pink orthoclase feldspar and green epidote.

Another attractive material is the

mineral rhodonite. Pink to red colored, its name is derived from

the Greek word for rose, rhodon, which aptly describes its distinctive

rose-pink color; the stone also usually has inclusion patterns

of black manganese dioxide. Although it is found wordwide, most

gem quality material comes from Australia, but also Russia, Vancouver

Island (Canada), and Brazil; it is also common in the US (it's

the state gem of Massachusetts), eg, the top center stone is from

Oregon. Although not as tough as microcrystalline quartz, with

a hardness of 5.5–6.5, rhodonite cabs take a good polish

and are very suitable for jewelry.

Another attractive material is the

mineral rhodonite. Pink to red colored, its name is derived from

the Greek word for rose, rhodon, which aptly describes its distinctive

rose-pink color; the stone also usually has inclusion patterns

of black manganese dioxide. Although it is found wordwide, most

gem quality material comes from Australia, but also Russia, Vancouver

Island (Canada), and Brazil; it is also common in the US (it's

the state gem of Massachusetts), eg, the top center stone is from

Oregon. Although not as tough as microcrystalline quartz, with

a hardness of 5.5–6.5, rhodonite cabs take a good polish

and are very suitable for jewelry.

Fluorite is prized for its glassy

luster and rich variety of colors, but is not commonly used as

a gemstone becaue of its low hardness (4 on the Mohs scale) and

ready cleavage. However, it can be used in jewelry such as pendants

which are not subject to significant wear. A significant percentage

of fluorites have colors arranged in bands or zones, as in the

banded purple fluorites shown below.

Fluorite is prized for its glassy

luster and rich variety of colors, but is not commonly used as

a gemstone becaue of its low hardness (4 on the Mohs scale) and

ready cleavage. However, it can be used in jewelry such as pendants

which are not subject to significant wear. A significant percentage

of fluorites have colors arranged in bands or zones, as in the

banded purple fluorites shown below.

Turritella (a fossiliferous limestone

found in Texas and California) was named by rock hounds after

the silicified shells it contains - tightly coiled. elongated

spiral cones from sea snails of the genus Turritella (these snails

originated in the Cretaceous period, 145 to 65 million years ago,

and are still widespread in today's oceans). However, most of

the "turritella" now available in the US comes from

an area in the Green River Formation south of Wamsutter in Sweetwater

County, Wyoming; it displays amber gold or blue to gray shell

outlines on a dark brown to grayish black matrix, as in the top

two cabs in the left pic. And recently, paleontologists have determined

that this Wyoming sedimentary rock was deposited at the bottom

of an ancient freshwater lake some time in the Eocene (between

53 and 42 million years ago), and that the fossil shells it contains

are really from the freshwater genus Elimia (still abundant in

shallow lakes and streams throughout North America; the shells

of tiny freshwater shrimp often are visible as well). I'm not

sure where the bottom three cabs in the left pic are from, although

they may have been cut from (true) white Turritella limestone

found in the Rocky Cedar area near Elmo, Texas. The cabs in the

right pic are definitely a true turritella (also called crawstone),

found in a remote part of the Baja Peninsula near the town of

El Rosario, Mexico; in addition to turritellids (but from the

Pliocene, ie, ca 18 million years old), the shells of clams and

a horn coral called Flabellum also can be seen. (Among other famous

turritellid stones are one with a white to tan matrix that comes

from an area near Bordeaux, France, and a Miocene sandstone packed

with turritellids from an area called the Erminger Turritellenplatten

near the German city of Ulm.)

Turritella (a fossiliferous limestone

found in Texas and California) was named by rock hounds after

the silicified shells it contains - tightly coiled. elongated

spiral cones from sea snails of the genus Turritella (these snails

originated in the Cretaceous period, 145 to 65 million years ago,

and are still widespread in today's oceans). However, most of

the "turritella" now available in the US comes from

an area in the Green River Formation south of Wamsutter in Sweetwater

County, Wyoming; it displays amber gold or blue to gray shell

outlines on a dark brown to grayish black matrix, as in the top

two cabs in the left pic. And recently, paleontologists have determined

that this Wyoming sedimentary rock was deposited at the bottom

of an ancient freshwater lake some time in the Eocene (between

53 and 42 million years ago), and that the fossil shells it contains

are really from the freshwater genus Elimia (still abundant in

shallow lakes and streams throughout North America; the shells

of tiny freshwater shrimp often are visible as well). I'm not

sure where the bottom three cabs in the left pic are from, although

they may have been cut from (true) white Turritella limestone

found in the Rocky Cedar area near Elmo, Texas. The cabs in the

right pic are definitely a true turritella (also called crawstone),

found in a remote part of the Baja Peninsula near the town of

El Rosario, Mexico; in addition to turritellids (but from the

Pliocene, ie, ca 18 million years old), the shells of clams and

a horn coral called Flabellum also can be seen. (Among other famous

turritellid stones are one with a white to tan matrix that comes

from an area near Bordeaux, France, and a Miocene sandstone packed

with turritellids from an area called the Erminger Turritellenplatten

near the German city of Ulm.)

Go to Gems-1 | Go to Gems-2

| Go to

Gems-3 | Go

to Wire-wrapped Jewelry | Return to Home Page

Go to Gems-1 | Go to Gems-2

| Go to

Gems-3 | Go

to Wire-wrapped Jewelry | Return to Home Page