CENTRAL OREGON

(Last updated 12/9/07)

The formation of Oregon started about 200 million

years ago (mya) when the floor of the Pacific Ocean (expanding

along a SW to NE diagonal rift) collided with the North American

continent between the Klamath Mountains (then an island) and the

Hell's Canyon area on the Idaho border; the range of "coastal"

mountains initially formed can still be seen in the Blues and

Wallowas. This situation persisted until about 35 mya, when the

rift in the sea floor shifted to a line paralleling the present

coast and triggered episodes of explosive volcanic activity in

the western Cascades. These episodes lasted nearly 10 million years and covered

much of central Oregon with a layer of ash called the John Day

Formation, in some places to a depth of almost 1000 feet. Then

about 20 mya, volcanic activity shifted to the central and eastern

part of the state where, for the next 10 million years, molten

lava flowed from fissures in the earth's crust and incredible

quantities of basalt flooded nearly all of Oregon east of the

Cascades. The resulting blanket of lava, the second largest basalt

mantel in the world, covered over 10,000 square miles of the state

to a depth of several thousand feet, producing Oregon's high desert

plateau.

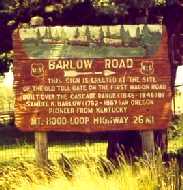

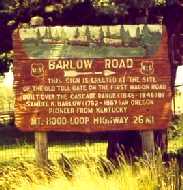

The historic one-room Smock Prairie

Schoolhouse (left) was recently moved to the town of Wamic, in

the foothills just west of Tygh Valley in Wasco county, and is

now a museum; an old, hand-carved sign (center) indicates that

Wamic is located near the first toll gate on the Barlow Road (1845-6;

the first overland route at the end of the Oregon Trail, the Road

wound over the Cascades through the TV from The Dalles to Oregon

City). White River Falls State Park, just to the east of TV, contains

the ruins of an historic hydroelectric plant (right), built in

1902 on a now dry tributary of the White to provide power for

the Wasco Milling Company in The Dalles (30 miles to the north);

the plant was expanded in 1910 after it was bought by PP&L

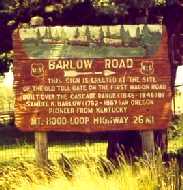

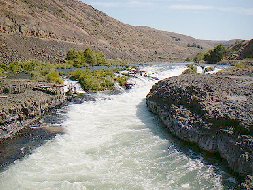

Over the eons, the lower Deschutes

River [from "Riviere des Chutes," or River of the Falls,

coined by French fur traders during the early 1800s - a reference

to the proximity of the river's mouth to Celilo Falls (now covered

by the pool of the Dalles Dam; see Gorge)]

has cut a wide canyon more than 100 miles long and 2,000 ft deep

through the accumulated layers of rock. These

views are from a stretch of river about 10 miles south of Maupin

[located in the central canyon (on Hwy 197) at one of the few

access points to the lower stretch of the river]. One surprising

aspect of the canyon is the single track railroad line that runs

down its west side (left), the result of a railroad war (1909-11) between James J. Hill's Oregon

Trunk Railroad, a subsidiary of the Great Northern line, and Edward

H. Harriman's DesChutes Railroad, a Union Pacific subsidiary;

the war was waged with rifles and black powder between competing

crews that numbered in the thousands as they blasted into the

canyon walls and raced to lay track on opposite sides of the river.

The road on the east side of the canyon (right), which provides

access to the river for anglers and rafters along 35 miles of

the canyon in the Maupin area, occupies the railroad bed of the

war's losing side

Over the eons, the lower Deschutes

River [from "Riviere des Chutes," or River of the Falls,

coined by French fur traders during the early 1800s - a reference

to the proximity of the river's mouth to Celilo Falls (now covered

by the pool of the Dalles Dam; see Gorge)]

has cut a wide canyon more than 100 miles long and 2,000 ft deep

through the accumulated layers of rock. These

views are from a stretch of river about 10 miles south of Maupin

[located in the central canyon (on Hwy 197) at one of the few

access points to the lower stretch of the river]. One surprising

aspect of the canyon is the single track railroad line that runs

down its west side (left), the result of a railroad war (1909-11) between James J. Hill's Oregon

Trunk Railroad, a subsidiary of the Great Northern line, and Edward

H. Harriman's DesChutes Railroad, a Union Pacific subsidiary;

the war was waged with rifles and black powder between competing

crews that numbered in the thousands as they blasted into the

canyon walls and raced to lay track on opposite sides of the river.

The road on the east side of the canyon (right), which provides

access to the river for anglers and rafters along 35 miles of

the canyon in the Maupin area, occupies the railroad bed of the

war's losing side

Sherars Bridge (left) carries Hwy 216

across the Deschutes about 10 miles north of Maupin - it stands

about 50 miles from the mouth of the Deschutes at the site of

a toll bridge built by John Todd in 1860, where a basalt flow

tightly pinches the river; Joseph Sherar purchased the bridge

from Todd in 1871, then built approach roads down the canyon walls

and a 3-story tavern/inn nearby that was a major stop for travelers

until 1905. A view of Sherars Falls (right) shows the force of

the river as it carries on the slow proces of cutting its way

through another layer of hard basalt.

Sherars Bridge (left) carries Hwy 216

across the Deschutes about 10 miles north of Maupin - it stands

about 50 miles from the mouth of the Deschutes at the site of

a toll bridge built by John Todd in 1860, where a basalt flow

tightly pinches the river; Joseph Sherar purchased the bridge

from Todd in 1871, then built approach roads down the canyon walls

and a 3-story tavern/inn nearby that was a major stop for travelers

until 1905. A view of Sherars Falls (right) shows the force of

the river as it carries on the slow proces of cutting its way

through another layer of hard basalt.

Sherars Falls is lined with rickety

platforms projecting over the river (left), from which Native

Americans use long-handled dip nets (right) to catch fish; only

tribal members from the Warm Springs Indian Reservation have the

rather dangerous privilege of fishing this way

Sherars Falls is lined with rickety

platforms projecting over the river (left), from which Native

Americans use long-handled dip nets (right) to catch fish; only

tribal members from the Warm Springs Indian Reservation have the

rather dangerous privilege of fishing this way

Shaniko (supposedly the local Indian

pronunciation of pioneer rancher August Sherneckau's name) is

a not-quite ghost town (population around 40) located on US Hwy

97 about 20 miles southeast of Maupin and 70 miles north of Bend.

Shaniko was planned and built (1900) by businessmen in The Dalles

as the terminus for the Columbia Southern Railroad, and as a collection

station for the enormous quantities of wool being produced in

central Oregon - a role it played into the '40's. The Shaniko

Hotel (1900; left), a recently restored 2-story building with

18-inch thick walls made of handmade brick, has become a popular

destination, as it was for this convertible club during Shaniko's

Pioneer Days celebration; the Post Office (right) also opened

in 1900

Shaniko (supposedly the local Indian

pronunciation of pioneer rancher August Sherneckau's name) is

a not-quite ghost town (population around 40) located on US Hwy

97 about 20 miles southeast of Maupin and 70 miles north of Bend.

Shaniko was planned and built (1900) by businessmen in The Dalles

as the terminus for the Columbia Southern Railroad, and as a collection

station for the enormous quantities of wool being produced in

central Oregon - a role it played into the '40's. The Shaniko

Hotel (1900; left), a recently restored 2-story building with

18-inch thick walls made of handmade brick, has become a popular

destination, as it was for this convertible club during Shaniko's

Pioneer Days celebration; the Post Office (right) also opened

in 1900

The 3-room Shaniko School (left), which

housed kindergarten through high school, was built in 1901; the

wooden Water Tower (1900; right) contained two 10,000 gallon wooden

tanks to hold water pumped from nearby Cross Hollow canyon, which

was then sent to the town through a wooden pipe system

The 3-room Shaniko School (left), which

housed kindergarten through high school, was built in 1901; the

wooden Water Tower (1900; right) contained two 10,000 gallon wooden

tanks to hold water pumped from nearby Cross Hollow canyon, which

was then sent to the town through a wooden pipe system

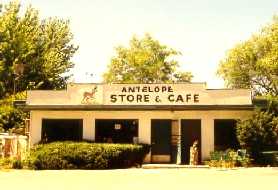

The town

of Antelope (about 8 miles south of Shaniko on Hwy 218; left)

was the first settlement in the Antelope Valley region; the town

warranted a post office (Howard Maupin, postmaster) by 1871, and

was a center for cattle and sheep men in the 1890's; destroyed

by a fire in 1898, it was quickly rebuilt, but nevertheless became

a ghost town after Shaniko was established. The hills to the southwest

of Antelope (near the Big Muddy Ranch, which was known as the

Rajneeshpuram in the 1980s) provide a view of Mt. Jefferson and

other Cascade peaks

The town

of Antelope (about 8 miles south of Shaniko on Hwy 218; left)

was the first settlement in the Antelope Valley region; the town

warranted a post office (Howard Maupin, postmaster) by 1871, and

was a center for cattle and sheep men in the 1890's; destroyed

by a fire in 1898, it was quickly rebuilt, but nevertheless became

a ghost town after Shaniko was established. The hills to the southwest

of Antelope (near the Big Muddy Ranch, which was known as the

Rajneeshpuram in the 1980s) provide a view of Mt. Jefferson and

other Cascade peaks

A series of three dams block the Deschutes

River at the south end of the Warm Springs Indian Reservation.

Two large tributaries, the Metolius and Crooked Rivers, join the

Deschutes behind 400-ft high Round Butte Dam (left; constructed

in 1964) to form one of the more surprising and spectacular aspects

of the high desert, Lake Billy Chinook (right), named after a

Wasco Indian who guided the Freemont expedition of 1843 thru this

area.

A series of three dams block the Deschutes

River at the south end of the Warm Springs Indian Reservation.

Two large tributaries, the Metolius and Crooked Rivers, join the

Deschutes behind 400-ft high Round Butte Dam (left; constructed

in 1964) to form one of the more surprising and spectacular aspects

of the high desert, Lake Billy Chinook (right), named after a

Wasco Indian who guided the Freemont expedition of 1843 thru this

area.

The three arms of LBC, which fill the

deep canyons originally formed by these three rivers near their

confluence, provide 72 miles of shoreline and almost 4000 acres

of water with an average depth of over 100 ft. Watersking, fishing,

and houseboating provide year-round recreation

The three arms of LBC, which fill the

deep canyons originally formed by these three rivers near their

confluence, provide 72 miles of shoreline and almost 4000 acres

of water with an average depth of over 100 ft. Watersking, fishing,

and houseboating provide year-round recreation

Looking west from the Peter Skene Ogden

Scenic Wayside (in Jefferson County, about 3 miles north of Terrebonne),

a view (left) of the 350-ft steel arched span of the Oregon Trunk

Railroad bridge (1911; designed by Ralph Modjeski) over the Crooked

River Gorge - one of the highest in the country, it rises 320

ft above the water; built

to complete the railway from the Columbia River to Bend, ownership

of the site (which Oregon Trunk bought from the Central Oregon

Railroad in 1909) turned out to be the deciding factor in the

Deschutes railroad war. Just upstream

(to the east) on US Hwy 97 is the spandrel deck arch of the 464-ft

long Crooked River Gorge Bridge (1926; right), designed by Conde

B. McCullough; the Bridge will soon be part of the Wayside park

as a new 4-lane highway bridge has just been built to the east

- a construction stay tower is still visible in the upper left

of this pic.

Looking west from the Peter Skene Ogden

Scenic Wayside (in Jefferson County, about 3 miles north of Terrebonne),

a view (left) of the 350-ft steel arched span of the Oregon Trunk

Railroad bridge (1911; designed by Ralph Modjeski) over the Crooked

River Gorge - one of the highest in the country, it rises 320

ft above the water; built

to complete the railway from the Columbia River to Bend, ownership

of the site (which Oregon Trunk bought from the Central Oregon

Railroad in 1909) turned out to be the deciding factor in the

Deschutes railroad war. Just upstream

(to the east) on US Hwy 97 is the spandrel deck arch of the 464-ft

long Crooked River Gorge Bridge (1926; right), designed by Conde

B. McCullough; the Bridge will soon be part of the Wayside park

as a new 4-lane highway bridge has just been built to the east

- a construction stay tower is still visible in the upper left

of this pic.

Just east of Terrebonne (and about

23 miles north of Bend on US 97), Smith Rocks State Park is an

international destination for rock climbers and the number one

sport climbing area in the country. Smith Rock proper (a ledge

of welded John Day rhyolite ash) is the southernmost

of the formations in the area, an imposing massif roughly 1/2

mile long surrounded on three sides by a hairpin loop of the Crooked

River.

Just east of Terrebonne (and about

23 miles north of Bend on US 97), Smith Rocks State Park is an

international destination for rock climbers and the number one

sport climbing area in the country. Smith Rock proper (a ledge

of welded John Day rhyolite ash) is the southernmost

of the formations in the area, an imposing massif roughly 1/2

mile long surrounded on three sides by a hairpin loop of the Crooked

River.

The highest peak in the area, The Summit,

is less that 1000 ft high, but sport climbing emphasizes technique

and physical conditioning rather than scaling great heights or

the use of artificial aids - although belay ropes are used for

safety. Thousands of routes (with ratings up to 5.14c), often

marked with the telltale of climbers' talc, have been mapped at

Smith, many of them short and near the ground, with fixed bolts

for anchor ropes permanently installed on more than a thousand

The highest peak in the area, The Summit,

is less that 1000 ft high, but sport climbing emphasizes technique

and physical conditioning rather than scaling great heights or

the use of artificial aids - although belay ropes are used for

safety. Thousands of routes (with ratings up to 5.14c), often

marked with the telltale of climbers' talc, have been mapped at

Smith, many of them short and near the ground, with fixed bolts

for anchor ropes permanently installed on more than a thousand

The names of various formations and

walls in the area - Asterisk Pass, Red Wall, Misery Ridge, The

Dihedrals - have become household words among the climbing fraternity

since a guide to the area was published by the Mazamas in 1962

The names of various formations and

walls in the area - Asterisk Pass, Red Wall, Misery Ridge, The

Dihedrals - have become household words among the climbing fraternity

since a guide to the area was published by the Mazamas in 1962

Return to

Home Page

Return to

Home Page